My sculptures are made of laminated cardboard and wire armature, covered with papier-mâché. The initial paper bulk is very simple, made from shredded paper (usually those nasty, unwanted credit card checks that banks send) and flour paste. The resulting material is so hard I have to use a reciprocating saw--the kind they use to take down buildings--to shape it.

I like to bury meaningful objects in my sculptures. Here I have left two voids where I will place two carved crystal Tibetan dorjes. Nagini's head has been removed. I decapitated her with my reciprocating saw because I did not like the original angle of the head and neck. When initially modeling, I tend to leave the wire armatures so that they can be moved until I am satisfied with the position of extremities.

I work outdoors in the hot months. Even when it is well over 100° here in Tucson, I prefer being out in the shade of the patio roof, looking at the mountains. I'm getting dirty anyway so a little sweat is no biggie. In the cooler months I tend to work indoors. Go figure.

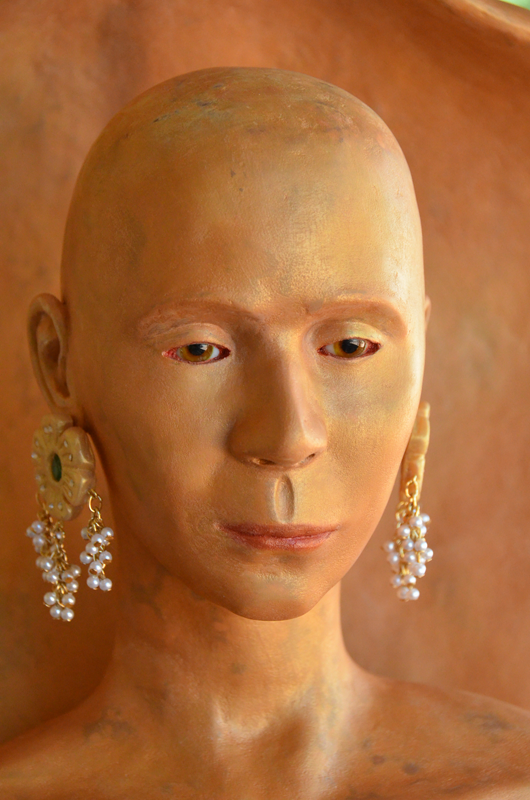

I found it easier to sculpt Nagini's head on a dowel, to be (re)placed later. She has glass eyes, which came from Greece. This shows the finer papier-mâché that I layer over the rough mixture of shredded paper. I use CelluClay. It has a relatively fine grain and is very workable. Used more sparely in this way, it is also not punishingly expensive.

This is my first sculpted human head (even though it's a snake-goddess and not a human). I have painted and drawn for a lifetime; sculpture is a much more recent undertaking.

A finer stage of modeling and yet another surface, blended from CelluClay and added material. I like to add substances that are 'sacred' and that will later be covered by a painted finish. The yellow color is from turmeric powder, which Indians use for many practical and religious purposes. I like that the skin of the goddess contains a hidden, ritually meaningful substance.

The cobra's cowl is made from laminated cardboard and a wire armature. Cardboard can easily be bent to make almost any curve or angle and is amazingly strong when laminated. Clamps and LOTS of wood glue are your best friends.

If you really want to get into it, alternate the grain of the cardboard, so that each layer is at a 90° angle to the previous. You can drop the finished piece from a building and it will bounce. (Not a great exaggeration, really! I know for sure you can drop a finished piece from 8' and only do minor patching to the surface. I've been there.)

The cardboard is covered with papier-mâché, then ground and sanded to a smooth surface. Another cherished friend: my Dremel tool.

Like the head, the cowl needed to be brought to a near-finished state before being mounted (by doweling and sinking the wire armature into the body) since the surface facing Nagini's back would be reachable only with difficulty. There is a strategy in how to assemble the pieces. If my strategy turns out to be wrong, I can always remove the section, like I did the head. This is an extraordinarily forgiving medium, and 'mistakes' can be made at any point of the process. Just fix 'em and keep going.

Nagini is gradually taking shape. She is shown here in a 5' high nicho I've been building for years now (same materials: laminated cardboard and papier-mâché; some wood at the spine since this is a very large piece. It's still not finished).

I originally thought I wanted Nagini to occupy the nicho, but eventually I added a floating stole and she no longer fits. I'll just have to make something else that will.

These are two 4" carved crystal Tibetan dorjes. They symbolize the masculine aspect of power that when united with the feminine, together make the cosmos move.

The dorjes are treated ceremonially: wrapped in red silk and bound in hemp twine, then wrapped in orange silk. The package will never be seen, but is nevertheless protected in a ritually-prepared package that keeps the crystal from being smutched by the sticky papier-mâché.

Powdered turmeric added to a loose flour paste.

The wrapped dorjes are finally protected by a layer of red wax, borrowed from my encaustics supply box. Red is is proper color for shrouding sacred implements.

The two waxed dorjes are spending a night with other ritual objects, including a Laotian shaman's spider rattle made of Mekong River mud, a cow pelvis from my brother-in-law's ranch (like my husband, he's also an artist) in Central California, and a small bowl of herbs.

The wrapped/waxed packets containing the crystal dorjes are inserted into the Nagini's spine, at the position of the Governing Vessel and Conceptual Vessel, according to Tibetan medicine. They will be sealed permanently inside.

The doweled cobra's cowl is secured by wired garden tape while the glue dries.

The first undercoat of paint has been added to the fine-sanded top layer of papier-mâché mixed with turmeric powder.

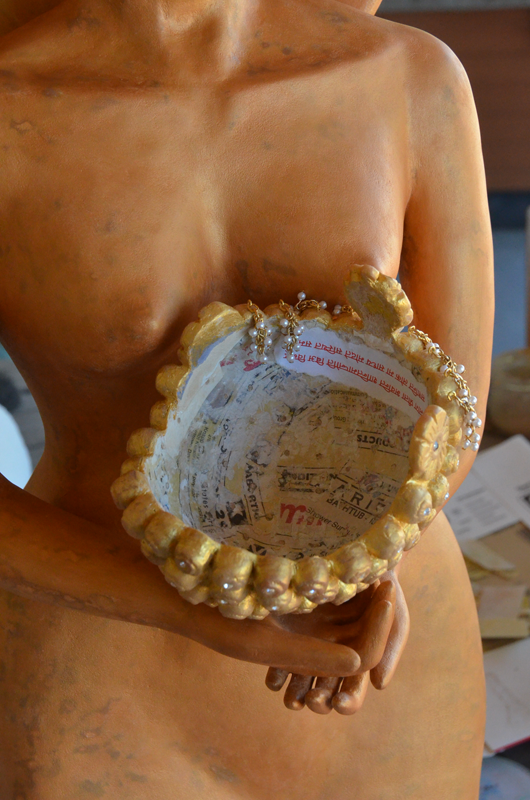

I sculpted a bead, then made a mold from SuperSculpey to cast each individual bead for Nagini's headdress. The molded regular Sculpey is dusted with dry Pearl-Ex mica pigment and a crystal rhinestone inserted into the top of each bead, then baked.

The beads are drilled and a toothpick inserted for a bit of extra holding power when I glue the beads in rows onto the crown. The crown was modeled directly onto Nagini's head with strips of newsprint wetted in flour paste. The head was protected by a layer of plastic food wrap. I shaped the crown so that it could be removed from the head.

The jewel and earrings are also made of Sculpey, with (artificial) pearls and lab-grown emeralds.

...just to make sure that the placement of the beads 'works.'

...row by row, by drilling, inserting the toothpicked and glued bead firmly. This took a while--but not quite as long as it did to make the beads themselves. Repetitive stuff gets boring fast, and it seems that every piece has a boring stage that simply has to be gotten through. What we sacrifice for art!

I want the final gold to have a lot of depth, so the underpainting is a deep, earthy brown, suited to the snake-deities' abode under the earth.

Domino the cat is my faithful studio assistant, indoors and out.

Pearl-Ex Brilliant gold, in an acrylic matte medium. It will be burnished with 400 (fine-grit) sandpaper. The initial sanding is mostly done with 60-, then 120-grit Dremel sanding wheels, and by whatever means possible in difficult-to-reach places. Sometimes emery board; sometimes strips of sandpaper. I've recently discovered sanding 'twigs'--and wish I'd known about them when I was sanding this project.

Hung with pearl dangles. Nagini's Sanskrit mantra is printed and glued inside so she continually can see her prayer through her Third Eye.

The inside of the crown is not varnished. It will eventually stick anyway because of the paint on her head, but the crown, strictly speaking, is removable.

The slight mottling of her skin texture is a happy accident, the result of layers of different colored materials, which inevitably went on in differing thicknesses on different parts of the surface, and were revealed in finish-sanding.

Nagini's lips and the corners of her eyes are painted with a wash of red kumkum, the vegetable powder used in India to make tilak marks on the forehead.

After the major work was completed, including the finish coat, it was then possible to add a floating stole. I first constructed it of flexible copper sculpting mesh, experimenting to get the curves and angles to complement the piece compositionally from all angles.

This is the first lawer of papier-mâché, worked into the mesh. The finish of the sculpture is (mostly) protected from scratching with plastic wrap and towels. Touch-up afterwards was thankfully minimal.

In order to add strength without a lot of bulk to the potentially vulnerable stole, I wrapped silk ribbon tightly around the first coat of papier-mâché. Lots of glue in this operation too. Wood glue is an amazingly strong substance, and if a little is good, a LOT more is even better!

A top coat of fine-grained papier-mâché mixed with sawdust from a mesquite tree on our property (another ritual touch). I wanted the gold on the stole to be of a similar brightness to the headdress, so I made the underlayer paler than the chocolate brown undercoat on the Nagini's body.

I've made the Nagini to be more human, feminine and compositionally simple and fluid than her lovely traditional counterpart. Instead of a conch, she holds a tarantula (this was my husband's brilliiant idea!) Like the Nagas, the tarantula is mythically chthonic, an underworld or under-earth dweller and a symbol of the Sonoran Desert.

The meaning of her name is “virgin daughter of the Nagas.” The Nagas are snake-beings, a very old part of Indic mythology, they appear in the Vedas (12th-10th cent. bce). In Hinduism and the pan-Himalayan indigenous religions, the Nagas are understood as a subterranean race, guardians of deep esoteric wisdom. They are especially associated with the Siddhis, magical powers displayed by yogis, shamans, monks, alchemists and other spiritually evolved truth-seekers. The Nagas are also known as the Guardians of the Rains, and are associated with the divinity of springs, wells, rainbows and underground rivers. Keepers of the Dharma treasures, they manifest a collective mind through a matrix of gems and crystals.

Similar beliefs with regard to the water-powers of the corúa, the serpent-guardian of springs and streams, are indigenous among the Piman Indians and the Mexicano communities in the Sonoran Desert, where I have my studio.